Minnesota's Alt-Meat Revolution: The Smell of Money

Minnesota's Alt-Meat Revolution: The Smell of Money

"The biggest thing for anybody coming in was ... there was a smell," remembered Bernice Oellien. "As one person said, 'It's kind of like a pig yard.' But I don't agree because I try to tell everybody it's a smell of money."

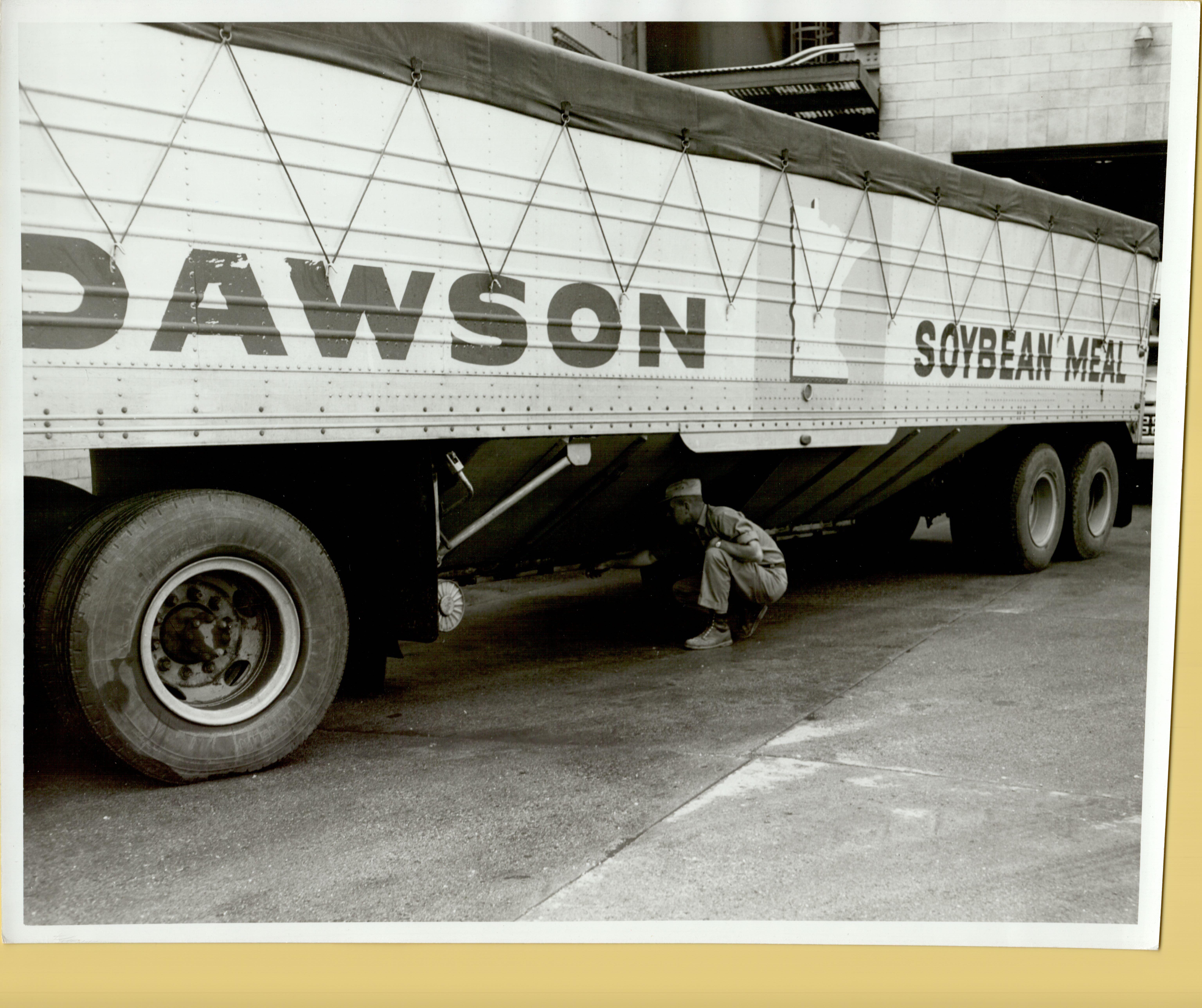

More and more people are getting their protein from non-meat sources, and the global plant-based protein market is anticipated to hit $17.4 billion by 2027. This series is exploring the roots and impact of the plant protein phenomenon that's exploding across the globe. A key part of that is playing out right here in Dawson, Minnesota, an agricultural town located in rural southwest Minnesota, population about 1,500.

"It's mostly soybeans and corn, and there's a lot of corn plants in the area also producing ethanol," explained Lee Gunderson, a retired Ag Processing, Inc. plant manager. "It's pretty open country so the wind blows around pretty good and we get some snow that blows around occasionally, it gets pretty deep."

Affectionately known as "Gnome Town" to locals, there are gnomes in Gnome Park to represent the founders of Dawson Mills, the company that was the originator of Dawson's signature smell. There is a hint of money, but the main smell, it's soybeans. You see, Dawson, Minnesota has played an important role in plant processing and in the development of plant-based proteins, which are exploding in popularity right now.

"So vegetarianism and diets that avoid flesh or certain kinds of meat have been around for since antiquity," explained Nadia Bernstein, a historian of food technology. "And there's a lot of reasons for vegetarian diets, spiritual, ethical, religious, concerns about health that have existed through history."

Our history starts in the Midwest where Henry Ford applied his ideas about industrial efficiency into plant-based products. Ford was a vegetarian and a huge backer of soy anything. There are photos of Ford modeling a soy suit and showing off a soy car. Ford worked with George Washington Carver to develop industrial applications of organic materials, a study that was referred to as "chemurgy." Carver also promoted soybean products as food for humans, not just for animals, an idea that Ford shared. Applying his industrial efficiency ideology, Ford was like, "If cows are making milk from eating soy meal, why not just skip the cow and get milk from plants?" In the 1940s, Ford's food scientist, Robert Boyer, developed a way to make a fiber-spun soy product that was initially used for textile fibers like the suit.

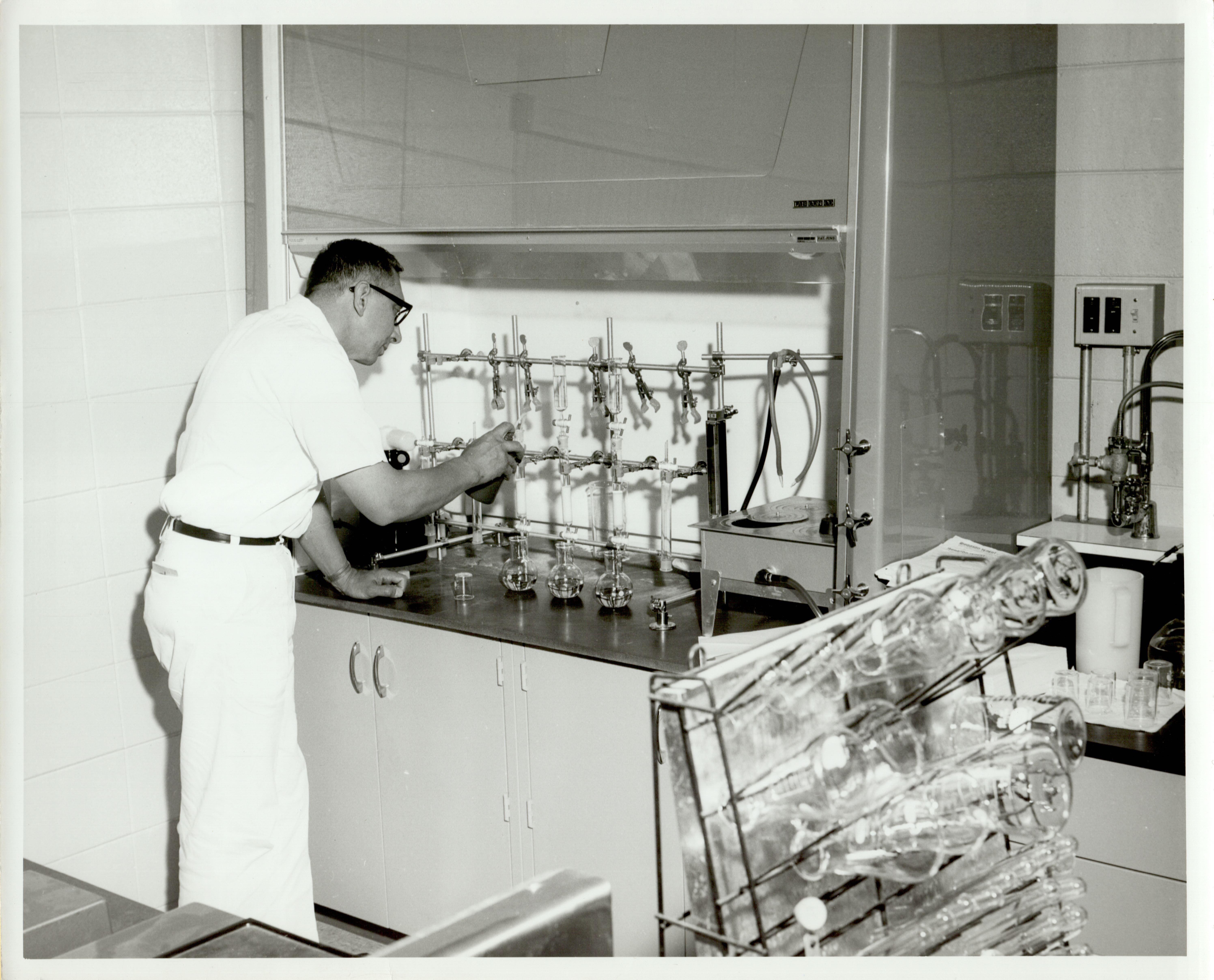

"The future of this technology was actually thinking beyond textiles," said Berenstein. "Boyer patented his technology for protein spinning. An entity that licensed this patent was General Mills. They had over 50 scientists and technicians working on this. Millions of dollars were invested in this in the sixties. They were essentially these bland, kind of chewy, blank canvases that could take on properties of different sorts of meat. General Mills called this product Bontrae. They were positioning Bontrae as a product that would benefit a world that was on the verge of environmental catastrophe."

People weren't thinking about climate change like we think about it today. The concern then was this very problematic concept called the "population bomb." Fiber spinning was GM's solution for an increasing world population that would be too taxing for meat production. But even though in the 1970s, when the cost of meat was really high, people didn't want Bontrae so people didn't buy Bontrae. So GM disassembled their protein spinning facility in Cedar Rapids, Iowa.

"That's where Dawson Mills comes in," said Berenstein.

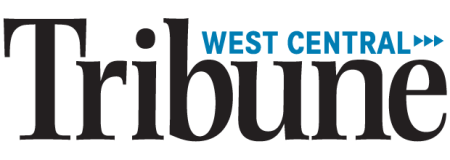

Before it was called Dawson Mills, it was the Tri-County Cooperative Soybean Processing Association located in Dawson, Minnesota – aka the town that reeks of money ... to some.

In October of 1954, four forward thinking businesspeople in town started talking about the business potential of soybean processing. They met for coffee in the local cafe and decided...

"Maybe they should look into establish some kind of a processing plant here," said local historian David Craigmile.

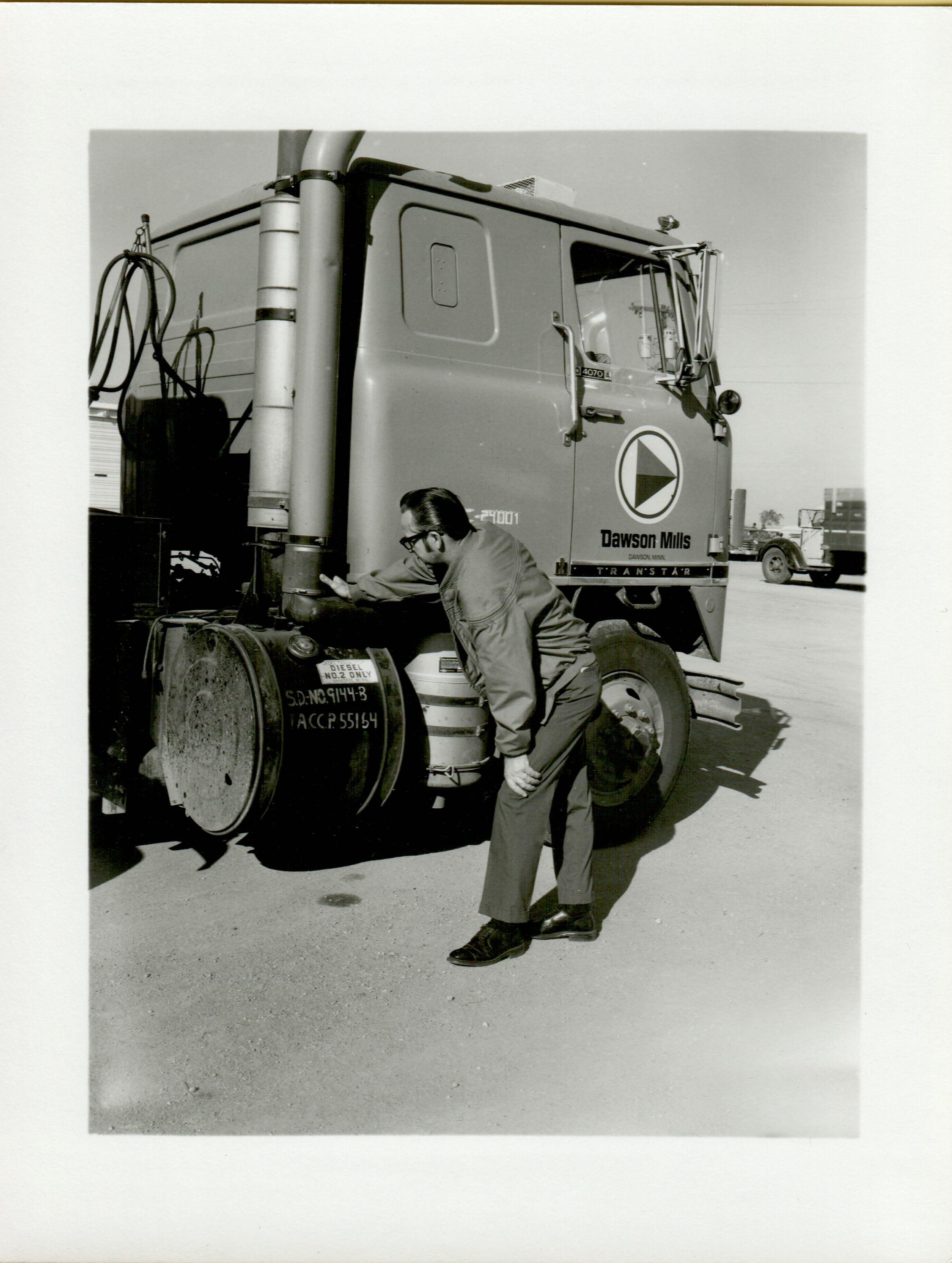

This brain trust studied soybean processing and in 1951, opened the Tri-County Cooperative Soybean Processing Association.

"It was fraught with challenges all the way through," recalled Craigmile.

From too much rain to financial instability, the plant experienced a number of growing pains but the main complaint came from cows. The plant used an extraction process to separate out the soybean oil. Once the oil was extracted, what was left was a soy meal cake that was mostly used for feeding cattle. That soy cake had a huge downside, it was killing the cows that ate it. The plant had to temporarily shut down while it fixed the problem and reopened in 1953. In the late 50s, things pick up and soybeans take off. Dawson started a soybean based festival in 1959. They had a pancake flipping contraption was arguably as hot as the pancakes themselves.

"That was a big event in Dawson when they made the pancakes using soy batter," remembered Oellien. "The grills had eight different plates on them like a carousel. The first one would put the batter on, and it would go around and they would flip 'em as they went. And it brought in people from all over the state to see this."

And by 1960, business almost doubled and the world got its first National Princess Soya in 1968. In 1969, the Tri-County Cooperative Soybean Processing Association renamed to the less descriptive, but easier on the tongue: Dawson Mills. Dawson Mills had been making soy flour for the government's Food for Peace program, but...

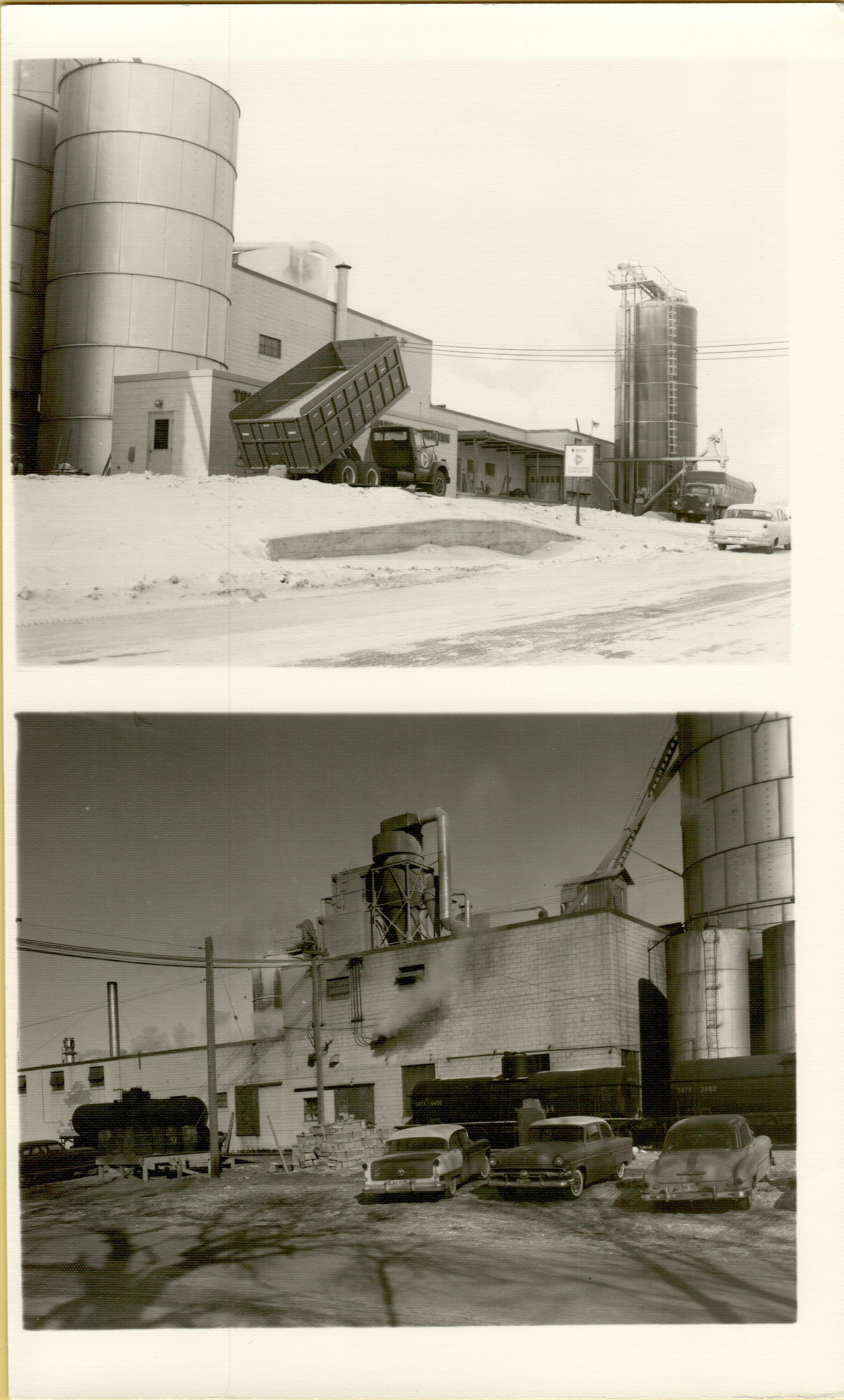

"They wanted to go a little further than that and also extract the protein and maybe get into a market where they would take this protein and use it as a substitute in for animal protein," said Craigmile.

"I don't know of anybody else that was doing isolating proteins other than whatever General Mills was doing," said Gunderson. "And Dawson Mills bought that plant equipment from them."

Dawson Mills also bought the rights from General Mills for Bontrae. In the heart of soybean country, Dawson Mills thought they could do what General Mills couldn't, market the meatless meat. This meant a bigger plant. Dawson Mills was located in the heart of town and expansion was nearly impossible. So they headed east, like one mile east.

"It was supposed to cost like $12-and-a-half million to build it and it got $20 million plus," said Gunderson. "So it was very difficult start and I mean there was a lot of talk about plant-based protein back in those days. They must have saw this coming and thought it's worth the try. You know, risk and reward."

But they stuck with it trying to market what they were calling Anaprime, fiber spun protein that had chicken, beef, and ham flavors. "The ham and the chicken was pretty good. It worked great in salads. The beef was a little, you know, maybe if you used it, I'm not sure what," said Gunderson.

That's his Minnesota nice way of saying people didn't like it, again. So Dawson Mills found itself in a General Mills situation. Their $20 million building wasn't producing a product that people wanted in 1979 or even knew how to use, it seemed to Bernice.

"We thought we're really gonna be doing something here and expanding and be helping the farmers out," remembered Oellien. "And I think maybe if we could have exposed people more to how to use it and what was really involved, it would've been better but that's hindsight, you just don't know."

By May of 1981, Dawson Mills' meatless meat dreams had come to an end. But their bean processing remained successful. And in 1984, after another merger, Ag Processing Inc or AGP took the reins and today is one of the largest employers in town. But that soy isolate building though, it also remained sitting alone in a field one mile east of town. From 1982 until 2012, it was an AMPI facility processing cheese sauces and other foods. When it closed, 130 people lost their jobs in Dawson. But what's old is new again and the facility in the field has new tenants and – wouldn't you know – with the company that manufactures plant-based pea protein, PURIS.

Had it not been for the foresight of a few local people trying to think differently about plant proteins or really, how they could get more value out of their soybeans, PURIS wouldn't have a facility to move into. "It's almost like Thomas Edison," said Craigmile. "He tried the filaments and the bulbs probably 400 times before he got what would work."

"The vegetable protein, I think it's something that's up and coming and when you're thinking about farmers, you know you're gonna be, are you yip yip hooray for the ones producing the vegetable protein or are you yip hooray for the ones that are producing the animal protein?" asked Gunderson.

How will the rise of plant proteins fit into our current agricultural, cultural, and dietary landscape? Do you have to be yip yip hooray for one or the other or is coexistence a possibility? "I don't know if we're ever gonna convert totally to plant-based protein and get rid of our animals. So I'm thinking that's gonna be a long, long time away," said Gunderson.

With a 75 million investment in PURIS from Cargill, could meatless meat in Dawson finally be a thing? In our next episode, we'll look at the landscape of plant-based protein manufacturers in Minnesota with a specific focus on the PURIS promise.